Ever been told that your feelings, your instincts, have no place in your analytics? That the only thing your gut can tell you is you’re hungry? I have. And you know what? I’ve been doing this for well over a decade now and the better I get at it and the more I do analysis in very tight time frames, the more I think that is complete nonsense.

I believe that if we actively try to ignore one part of our brain, disregarding our instincts and emotions, then we are no better analysts than if we just ignore the data completely and use guesswork alone. I believe that honing our instincts through practice and self awareness – and trusting those instincts at the right stage in the analysis process – is how we make the leap not only from reporting to meaningful analysis, but from a reductive worldview to an insightful one.

And I don’t think I’m alone. Last year Jim Sterne hosted a one day symposium on “How To Analyze.” A bunch of us old timers had just 10 minutes to distil the essence of analysis. Some of the concepts that kept coming up were distinctly emotional ones – curiosity, instinct, context, balance, openness, intuition, self awareness. As Jim summed up in a later blog post:

“Data is good. Data is valuable. Just don’t be black and white about it. You can use data to help you and you can use data to trap yourself.”

So in the rest of this post I want to share three practical things that work for me and that I feel make a positive contribution the speed and quality of my analysis:

- When your emotions (or gut) can be highly useful

- How to use those feelings

- Why practice and mental visualisation pays off

You may of course think they’re nonsense and that I am clearly a defective analyst. I welcome the debate!

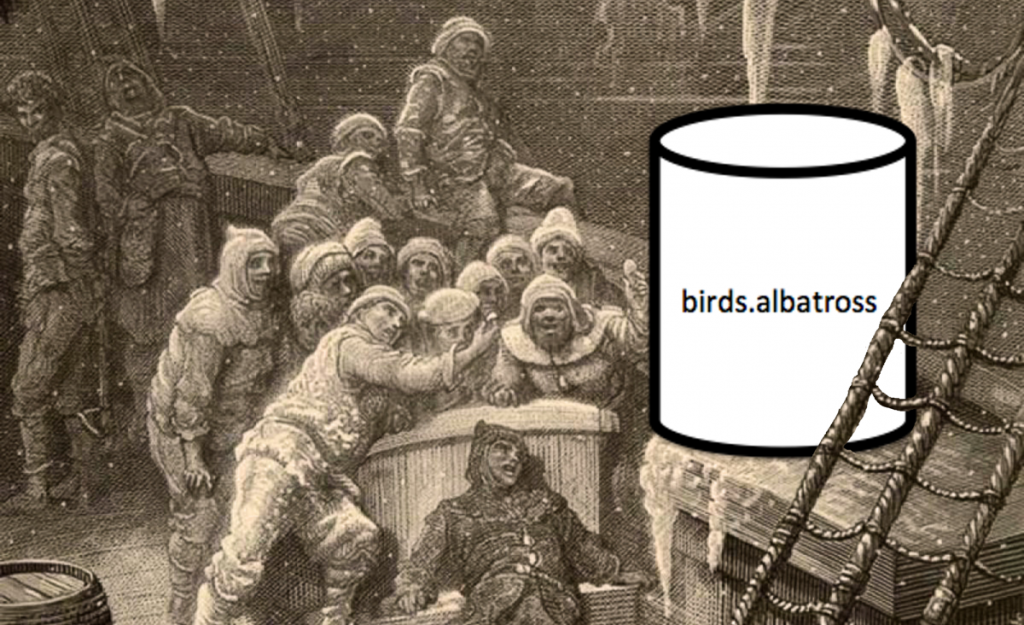

Why this graph made me sick – or when your gut can be useful

It looks pretty inoffensive, I realise, but the moment I saw this graph, the reaction was visceral. This graph made me feel sick:

Well before I could rationalise exactly why this graph was off, let alone systematically explore the data to understand precisely what had occurred, my emotional brain was giving me a specific message:

“caution, something’s off – start digging and wait before you share this with others”

Of a gazillion bits of data I could choose to look at, this leapt out and sent my emotional brain ringing with adrenalin – all triggered by the final data point on the above graph. My focus rapidly zoomed in on something different – a potential problem or change – and caused me to alter my subsequent behaviour. Just as importantly, it set the emotional tone for those explorations – not hooray, you just destroyed your target, but caution, proceed with care.

Not all “huh?” moments make you sick, but plenty of them start with “that’s interesting…”

And as an early warning system, that’s the emotional brain’s job done. Time to try and place it aside and stay in control, for now the rational work begins. I don’t want those emotions building a handy fiction from the data – the emotional brain has told me where to look, it is important I don’t also let it tell me what to find.

Who Cares?

It turns out that in this instance, the uplift in conversion and revenue was coming from a single source, a new reseller directing their substantial transactional activity through the public site. My gut alone could not have solved that, certainly not with verifiable evidence. But the data without the emotional input would have told a very different story too – a happy tale of up and to the right graphs, record revenue and new conversion highs. Without the two parts of the brain working together, without context and emotional input, there would be nothing seemingly wrong with the graph at all.

There’s also a post calculation emotional function that I find highly useful – less “so what?” and more “who cares?” Asking “who cares?” places your data firmly back into the reach of the emotional brain.

- Is this relevant to others?

- Will I get praise/rewarded for this?

- Does this information make someone else’s life better or worse?

- Could this affect someone’s behaviour?

- Can they use it for decisions?

- Do I need to frame it and communicate it in a way that will help them grasp it?

Once you start asking yourself these kinds of questions, it is my experience that you can’t help but have instinctive, connective emotional brain reactions. That, I suspect, is where reductive reporting ends and insight begins.

Practice, practice, practice

So emotions and instincts have their place – and in my opinion one of the best places is upfront, the shortcut to troubleshooting. But that early warning system doesn’t get useful on its own. Since I began reading extensively about how we think and decide, then analysing my own analytical thought process, I have realised that exposure to broad contextual data, practice and reinforcement of positive and negative outcomes contribute to the accuracy of that early warning system. And that this is something you can actively improve.

By practice I don’t simply mean time using an analytics tool, nor is it solely about exposure to lots of data How much time do you think about how you analyse? For example:

- How did you come to that really great conclusion?

- What about all the other possible ways you could have interpreted the exact same data? Why were they wrong?

- If the reverse conditions were true (sunny not cold, public holiday not Saturday, French not English) how would you interpret it then?

Personally (and I may be insane) I love visualising other possible scenarios and data worlds in my head and that is what I mean by practice. You get to play out what does and doesn’t work without getting fired.

Then there’s reinforcement. Have you ever come to the realisation that the thing you were so sure of a few months back, the thing you shared excitedly with your colleagues and they loved, was actually, well, plain wrong?

The reason the graph made me feel sick is because of this kind reinforcement. My brain learnt a valuable lesson when I was an analyst for HP – don’t be in such a hurry to share good news that you can’t fully explain. It will be very, very painful when you have to retract it.

When I saw the graph above, at an instinctive, emotional level I suspected it was probably too good to be true, or at least that I had no satisfying evidence of why it might be right. (That Google Analytics said so is not satisfying evidence!!) So my early warning system bleeps caution – proceed with care. If my fears are wrong, I still make everyone happy and get praise. If I’m right, I saved myself lots of pain. Win, win says my emotional brain.

As Johan Lehrer, author of How We Decide, Proust Was A Neuroscientist and The Neuroscience of Screwing Up, writes:

“What’s interesting about this system is that it’s all about expectation. Dopamine neurons constantly generate patterns based upon experience: If this, then that. The cacophony of reality is distilled into models of correlation. And if these predictions ever prove incorrect, then the neurons immediately readjust their expectations. The discrepancy is internalized; the anomaly is remembered. “The accuracy comes from the mismatch,” Montague says. “You learn how the world works by focusing on the prediction errors, on the events that you didn’t expect.” Our knowledge, in other words, emerges from our cellular mistakes. The brain learns how to be right by focusing on what it got wrong.”

This is learning and this is analysis too. So, to conclude, I feel that as analysts our brain is by far the most important tool we use. In which case examining our own thought processes, exercising that tool and using all the brain’s available parts is critical.